Electric Dreams: Art & Technology Before the Internet | Tate Modern

I was taken aback by the blissed-out optimism of this exhibition, which collects tech-oriented art from (roughly) the 1950s to the 1990s. The birth of the computer age led to new artistic possibilities: kinetic sculptures, algorithmicly-driven painting, computer-generated video art. The show made me realise that it also coincided with another cultural moment: flower power - peace and love - the dawning age of Aquarius. Hippies, basically.

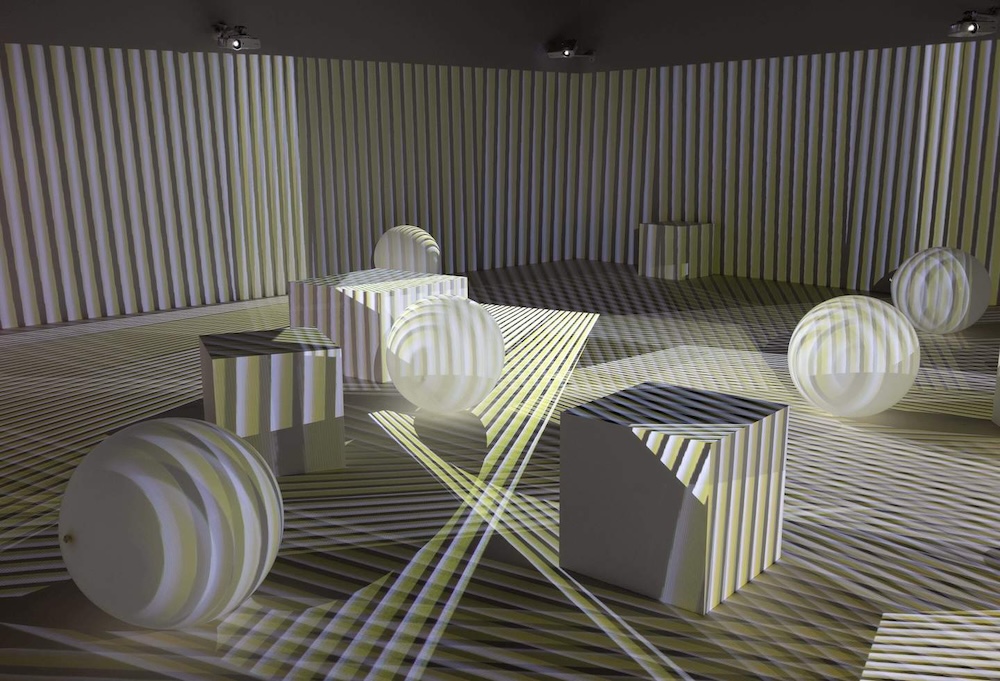

One room around half way through summed it up: Carlos Cruz-Diez’s Chromointerferent Environment, originally shown in the early 1970s. Primitive computer graphics strobed around the walls. Joyful kids bounced balloons around, casting shadows against the light, filmed by their phone-toting parents. Like so much else in the exhibition, the work’s vibe was one of collective fun - and possibility.

Image credit: Tate

Image credit: Tate

Despite its generally inclusive outlook, the production of this technology-driven art wasn’t very accessible at the time. The tech was so new and expensive that artists had to partner with research institutes and large companies to get access to it. Taking two artists featured in the Tate show as an example, video art pioneer Lilian F. Schwartz had a decade long residency at Bell Labs, while Waldemar Cordeiro, whose computer-generated graphics I’ve featured on here before, relied on his local university for both funds and materials.

Others turned to the private sector. The Tate show featured a (for me, at least) fascinating project from the art collective Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), which collaborated with PepsiCo for a sponsored pavilion at the 1970 world Expo in Japan.

Image credit: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Image credit: Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

The collective, which included Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman, was founded with aims that seem wildly optimistic and progressive in hindsight. While we in 2025 worry about generative AI taking our jobs and bitcoin taking out our financial markets, EAT aimed to “eliminate the separation of the individual from technological change” and “encourage industrial initiative in generating original forethought”. At least, that’s according to their 1967 Statement of Intent, featured in a vitrine in Tate. It’s printed on paper, which has yellowed and frowsed over the decades.

Somehow the hippy collective persuaded a multinational soft drinks maker to pay them a spectacular amount of money (in the eight figures when accounting for inflation) to build an avant-garde tech-oriented immersive art pavilion. Perhaps aggressive flattery helped? As the collective’s press release announcing the project stated: “EAT is interested in Pepsi-Cola, not art. Our organization tried to interest, seduce and involve industry into participating in the process of making art.”

To achieve this aim, the pavilion, an appropriately space-age white dome, came replete with laser and sound installations, a “fog sculpture” engulfing its exterior, and a movement-activated soundtrack played to visitors via cutting-edge portable handsets. On the inside, the pavilion was mirrored on the ceiling; the floor was clad in stone, wood, carpet - and artificial grass.

Just like the peace-and-love era, the pavilion didn’t last long. EAT’s very own Altamont came just a few weeks after the ribbon was cut. After building up unsurprisingly irreconcilable differences with the rather more straight-laced Pepsi executives in control of the budget, the artists were sent home. But the fact they were invited at all seems incredible.

What did visitors make of the pavilion at the time? At Tate, there’s archive footage of Expo-goers - very ordinary looking, sensibly clad Japanese families - entering the pavilion. They are given big plastic handsets. The children bounce through the fog and lasers joyfully, staring up at the huge mirrored dome with mouths wide open. They reminded me of the posh English kids punting Cruz-Diez’s balloons around a few rooms away.

They’re jointly responding to a shared artistic mindset, embracing technology that would have been so new and exciting back then, but is so deeply quaint now. And embracing technological progress in a way that seems extraordinary in these cynical and suspicious times. I found it all very uplifting.

Electric Dreams: Art & Technology Before the Internet is at Tate Modern (London). 28 November 2024 - 01 June 2025