Interlude - Wade Guyton at MoMA

How unsatisfying to look at art on a computer screen, rather than in a gallery. Unsurprisingly, considering I go to 200+ shows per year, I’ve fallen in love with the whole ritual of gallery going: ringing the bell, taking the printed-out press release, writing in the artist’s book on leaving. And now, how quaint that seems in virus-induced lockdown: bell, paper and pen have all become potential vectors of disease, in my mind’s eye.

So I’m left with digital reproduction, alone in my flat. That can never be a perfect transfer of the real thing - it blurs, crazes at the edges; it washes out some colours and oversaturates others. Last week I started an experiment - in the absence of shows to see, I’m discussing a work in a permanent collection I’ve been thinking about instead. For my first post on that theme, Rogier van der Weyden’s Columba Altarpiece, I was disgusted at the shoddiness of the image of the work I was forced to use, for lack of a better alternatives. Truly, nothing like the real thing.

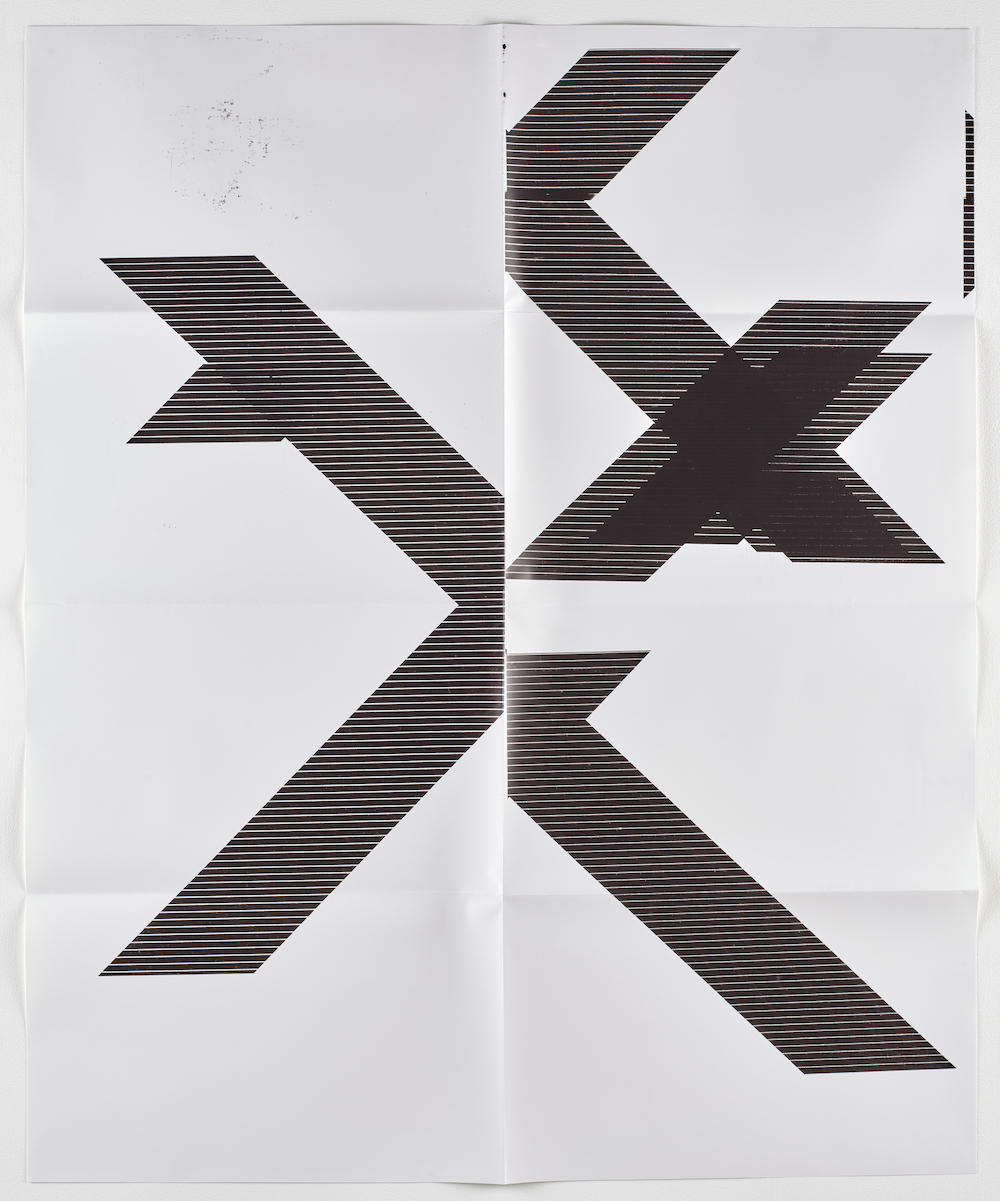

For Wade Guyton though, the subject of this week’s post, the imperfection of the reproduction is the whole point. I saw a show of his last year at Chantal Crousel in Paris: works, all untitled, that were formed by printing a downloaded image from the internet, over and over, leading to strange distortions, striations and disjunctions.

In Paris, Guyton cheekily used video stills from internet porn sites as source material: the original sex act was filmed, reproduced, then pirated and reproduced on XVideos, then screencapped by Guyton and reproduced several more times over, to make the outlines of the original performance ghostly, faintly lyrical.

But in the work above from the permanent collection at MoMA in New York - it’s called, prosaically, X Poster, Guyton keeps things simple. The original black letter is smudgily reproduced, the tell-tale horizontal lines from cheap inkjet printing deeply engraved. And then the letter itself is split up, multiplying in a strange shadow play across the page.

It lends the whole work a faintly sinister ambiance: a sense of quiet breakdown, a quiet rebellion of an office printer, garbled advertising poster. And, today, looking at these works in reproduction, there’s a further irony: the world’s printers have ground to a halt, and are gathering dust in offices emptied by the virus. All of that paper work is now digitised. Just like my appreciation of Guyton’s art.

X Poster is in the permanent collection at MoMA, New York