Jörg Immendorff - Questions from a Painter Who Reads | Michael Werner

This is an artist who was a really big deal in his native land. I first heard of Jörg Immendorff when I visited his enormous retrospective at the Haus der Kunst in Munich last year, spanning his early political paintings of to his complex, gloomy, finely-wrought late works, painted as the artist was dying of ALS. A hideous way to go - and he went in 2007.

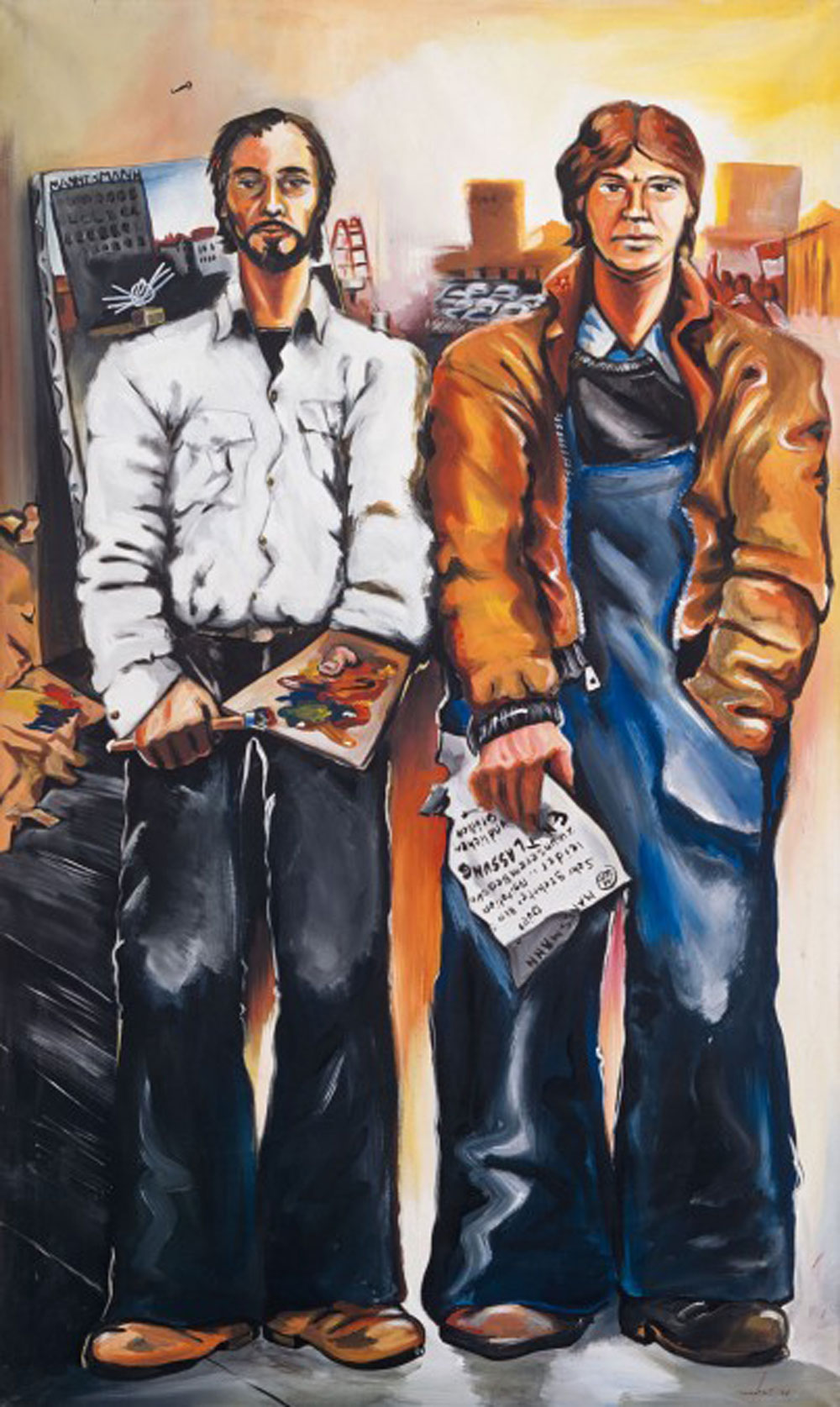

Now, Michael Werner is showing a cycle of huge paintings from the final year in its lovely winter garden, with some other examples of another Immendorff period - his fervent and optimistic 70s paintings of heroic workers and artists, working together to trash capitalism in some impressive wing collars and flares.

Immendorff suffers from his attachment to - from the perspective of the comfortable 21st century West - obscure causes (hardcore Marxism) and forgotten struggles (German reunification). And, throughout, along with monumental scale, his works are also handicapped by his inscrutable humour.

I don’t get the joke. Not so much due to the silly stereotype that Germans aren’t funny, but because he’s funny in a way that’s mysterious to this British viewer. In stark contrast to the more digestible larkiness of his compatriot and contemporary AR Penck, who had a revelatory show at the same gallery last year.

But then again, there’s something fascinating in his lost 70s world of Communist struggle. Mannesmann - Entlassung shows the artist side by side with a factory worker, both sporting some spectacular examples of the decade’s pointy collars and billowing flares. You can practically hear the polyester crackle.

It all ended in disillusionment: Parlament, painted just two years later, shows an assembly of wolves - politicians of all ideologies clearly disgusted him by then.

The deliberate crudeness and boldness of Immendorff’s brushwork is all gone by that final cycle in the winter garden: the finer grain depictions of strange half-men-half-beasts are offset by the artist’s final act, deep into a remorselessly degenerative neurological disease: a random-seeming disfigurement of splotches of thick, black paint. Death is universal; senses of humour aren’t.

Other Highlights

I saw a lovely selection of mixed media works from Italian artist Carlo Rea at Tornabuoni Art: plaster petals painstakingly glued on to monochrome canvases, the overall effect being as if it’s bursting open with flowers. Just as pretty was the UK’s first show of fine art photographer Irving Penn’s paintings at Hamiltons. Generally from late in the photographer’s career, they’re layered abstractions, inspired by Léger and Matisse, built from a base of inkjet print reproductions of day to day objects to become something surreal and strange.

Elsewhere, Milan-based Pietro Roccasalva showed a set of paintings of total Italianness at Massimo De Carlo (which seems to be sharing its premises with a high-end carpet dealer?): based on a film still from the Pasolini movie La Ricotta’, and often featuring what looks very much like Morandi’s white bottle.

I loved conceptual artist and ex Marina Abramovic paramour Ulay’s fun “polaroid paintings” at Richard Saltoun, and, to bookend the week with more Germanness, was baffled by André Butzer’s “science fiction expressionism” at Max Hetzler’s new London space.

Jörg Immendorff: Questions from a Painter Who Reads is at Michael Werner (London). 16 November 2018 - 25 January 2019