Mario Sironi - Signs and Colours | Brun Fine Art

This exhibition begins with a surprising painting, considering its painter: a smiling self-portrait. Surprising, as Mario Sironi’s reputation is based his unremittingly grim work, spanning the early 1920s to the 50s. This general bleakness, coupled with his enthusiastic embrace of the Mussolini regime pre-war, and his post-war withdrawal from the public sphere, has made him a pretty obscure name - especially in the UK, where this is the first Sironi show in memory.

The span of the works is admirably comprehensive, covering everything from some mystical - or metaphysical - early de Chirico-style paintings, to his lucrative ad illustrations in mid-career, to some truly terrifying black and red monoliths from the later years. Faced with a dethroned Duce and a family tragedy, he retreated from the world after the war.

I’ve written before about a section of his oeuvre that I really love: his grimy suburban Paessagi Urbani of the early 20s, loving and sinister portrayals of suburban factories, smokestacks, and motor traffic.

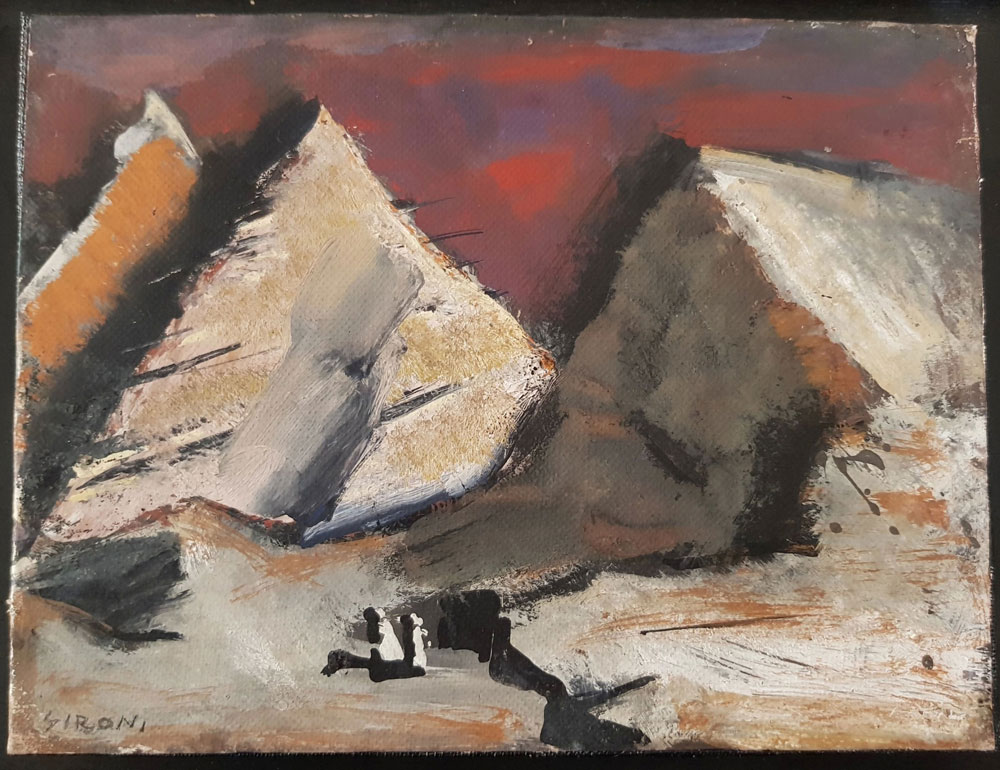

Things changed later. Check out Mountains from 1952, above. The crags are savagely pointed, the sky blood-red. Still and sinister, they loom out of the small canvas.

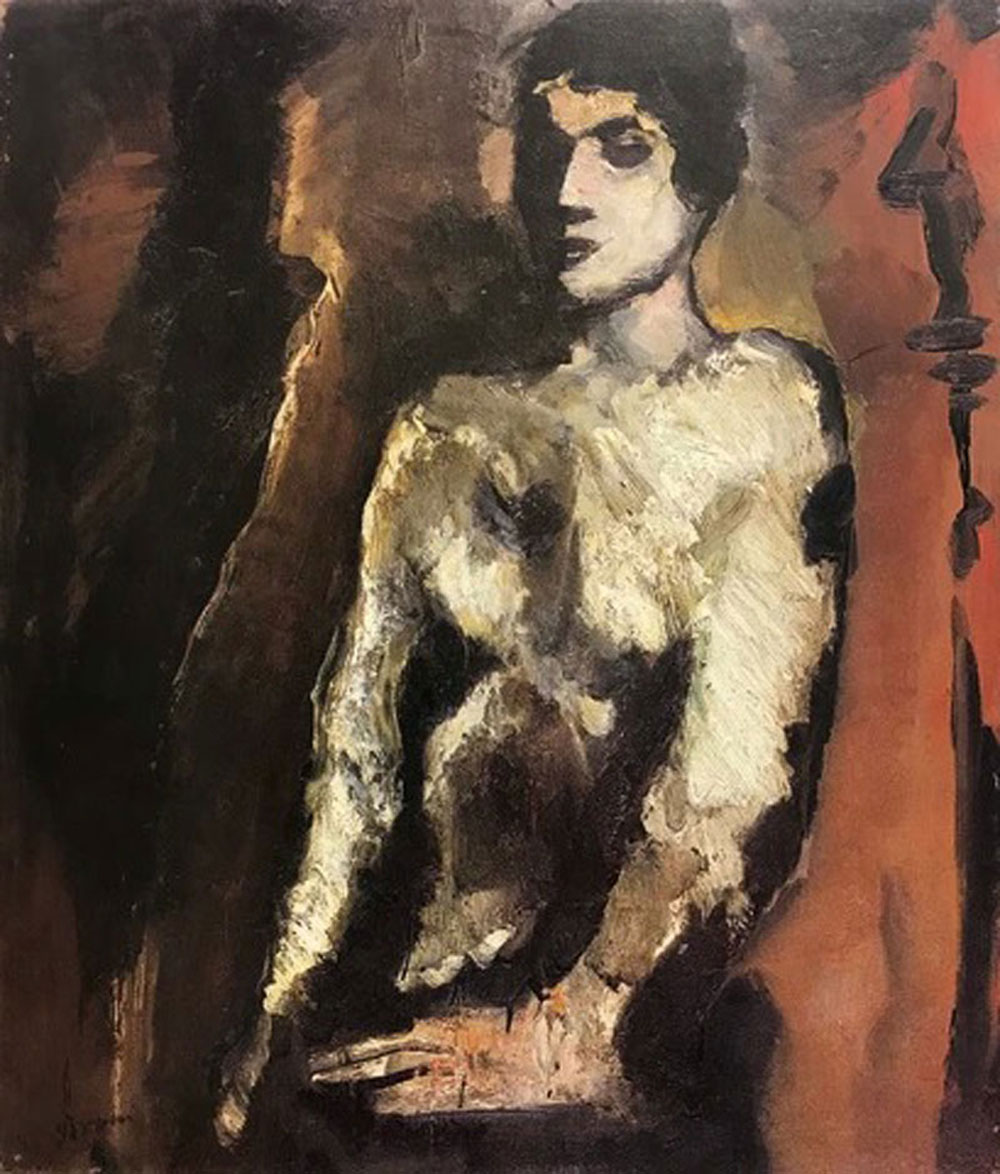

There’s a monolithic crudity about the portraits, too.

What an elusive and crafty portrait Seated Figure, from 1930, is. The female subject as boldly rendered as a Corot, with those big black outlines. But it’s thrown out by the massive, clunking, pinkish left hand, laid out flat in the foreground. The underlying craft giving the viewer the sense of this haughty woman is blurred and blotted by seemingly careless gesture.

The advertising illustrations elsewhere in the show, for Fiat among other clients, prove that Sironi the draughtsman was capable of great delicacy and refinement. That’s certainly the work Sironi was most famous for in his early career. But they’re qualities that the painter, especially the post-war painter, was less interested in.

His portraits become less substantial in later years, almost as if they are disintegrating. They are often depicted floating in the air. Far from the neat canvases of Sironi-the-public-artist, they’re scrawled on paper, on newspaper, in exercise books.

The final work in the show is Figures from 1959, a couple of years before Sironi’s death. These black figures practically merge into the background; the artist’s signature is barely a scrawl. He seems past caring, but the underlying craft and skill makes the image distinctive and captivating all the same.

Sironi was celebrated enough in his home country during his lifetime to have been granted an extensive retrospective at the Venice Biennale, a year after his death in 1961.

Whereas in these small rooms in an upper-floor private gallery in Mayfair, I got the definite impression that not many people are coming to see the show. The gallerist certainly seemed surprised to see me visit. Piles of a quite lavish exhibition catalogue lay on every available surface.

It’s not likely I’ll see a retrospective of his in London again for many years, then. To which I feel an appropriately Sironi emotion: sadness.

Mario Sironi: Signs and Colours is at Brun Fine Art (London). 8 March - 24 May 2019.