Top 5 of 2021

I’ve surprised myself with sticking to the Artangled project for another year. Ever since lockdown eased in April, and many London galleries reopened, I’ve posted weekly. Just as I have each week since the beginning of 2018. This site, and its thousands of words, remain a personal project: I doubt I could ‘grow the brand’ even if I tried! But I should admit, it’s remained a personal pleasure to sit down each week and put together a post, and I’ll continue doing it as long as the pleasure remains.

Anyway, just as in 2018, 2019 and 2020, here’s a year-end roundup of five shows I featured on the site that I really enjoyed, five more close runners up, and one public gallery show that was a disappointment, just to prove I possess some measure of critical distance from my subjects.

In these year-end posts, I’ve also made a habit of rounding up the total number of exhibitions I’ve got to in the calendar year. Having maxed out at 256 in 2018, and seeing a healthy 221 in 2019, the pandemic and gallery closures saw the total drop to 84 last year. In 2021, it’s semi-recovered to 141 shows. I think three factors were behind this comparatively modest total: first, the fact that we began and ended the year with galleries closed due to COVID; second, I travelled less; third, I found myself being more selective and sparing with the shows I did see.

Here are my top five of those 141.

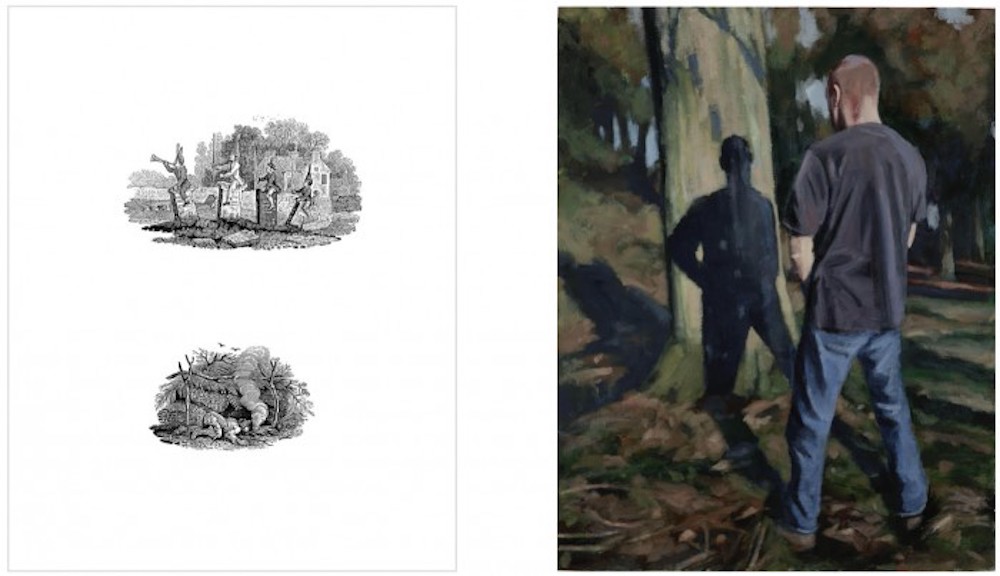

Children Riding Gravestones: George Shaw & Thomas Bewick (Laure Genillard, London)

George Shaw’s famous for painting scenes from the not-so-nice Coventry suburb he grew up in, using the kind of enamel paints more commonly used for model aeroplanes. Thomas Bewick was a 19th century wood engraver of beautiful pastoral scenes. This show was a minor curatorial triumph, in that it made such a convincing case for these apparently very different artists being kindred spirits.

Nobody who grew up in the English suburbs, me included, can fail to be captivated by Shaw’s scenes of collapsed wooden fences, pebbledashed semis with their encrustations of satellite dishes, and weak clay-like light. But the show highlights instead the hidden beauty of his paintings. And similarly, for the scabrous social criticism of Bewick’s etchings: he was an outspoken provincial outsider in his time, too. Both artists’ evocative portrayals of neglected nature amplified each other.

Hwang Seontae: The Power of Light (Pontone Gallery, London)

I kept asking myself, as I walked around this exhibition, are these lightboxes lovely or sinister? Are the spaces Hwang Seontae, a Korean artist, portrays waiting for people to arrive, or have they left? Were they never here? All of the works on show had the same title, The Space with Sunshine. Space is empty minus the expensive furniture; all the rooms are totally depopulated, which maybe explains the absolute orderliness of these interiors.

I couldn’t figure out to myself what it all ‘meant’ at the time, and still can’t. But I have to say, these sunny spaces still come to my mind. And I can’t wait to see what this artist gets up to next.

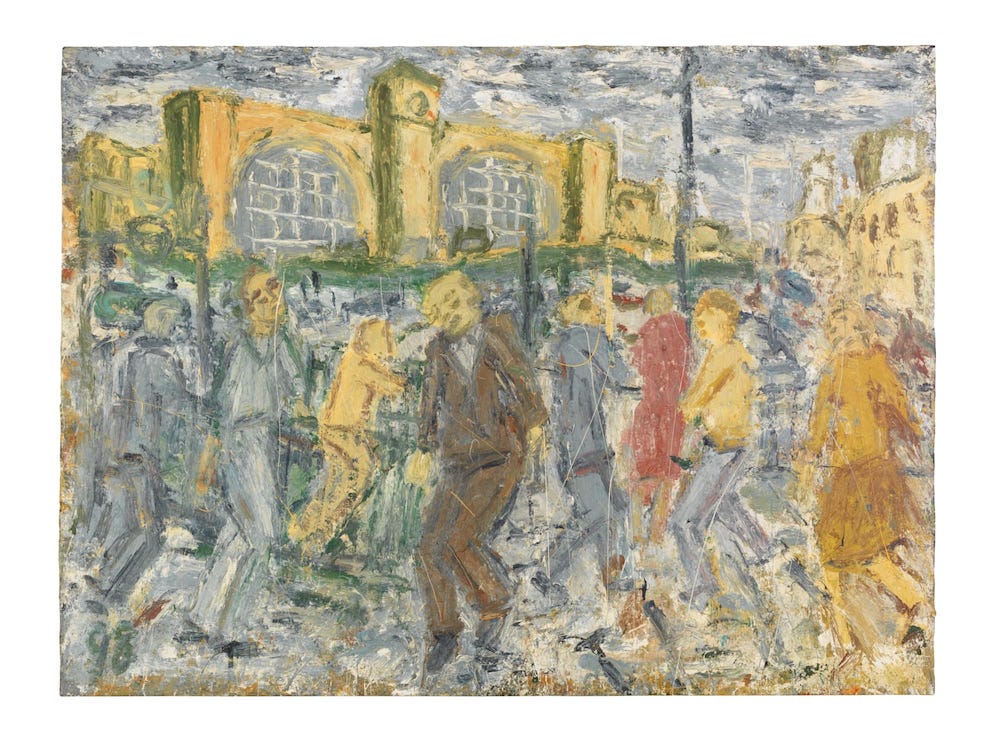

Leon Kossoff (Annely Juda Fine Art, London)

This was a fabulous mini-retrospective at a gallery known for its sensitive showings of midcentury British masters.

Kossoff’s subject matter is firmly rooted in the city he rarely left - London. The parts of the city that he liked to paint - from the train tracks at the end of his garden in Willesden to King’s Cross station (above) to a swimming pool in Crystal Palace - weren’t very glamourous. But the eye he cast on them always seems to have been humanistic and kind. His great landscapes use enormously thick wedges of oil paint, layered over and over, sticking out quite a way from the canvas. Viewed on a sunny day, the great landscapes, especially ones from the 1960s and 70s, were almost sculptural.

The layers thinned out towards the end: the exhibition has one of Kossoff’s very last pictures, of a cherry tree in his garden, and it’s almost ghostly. But his keen eye and profound sensitivity to light, and the city the light is cast on, stayed true throughout.

Shannon Cartier Lucy: Cake on the Floor (Soft Opening, London)

“The setting of a party can be inferred by the particular debris and signs of festivities: there is cake and strings of undulating, crimped satin ribbons, but the situation reads as ominous, toxic.” So state the show notes for this exhibition.

Or, as the iconic pop song has it, it’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to. Lucy’s fine paintings of women in distress use the full festive panoply of thickly-iced cake, silly string and flowers. This Nashville-based artist’s work made me think of Jenny Saville, with her close-ups of women in distress, and Wayne Thiebaud (RIP), that master of the expressive and sinister pastry. I’d love to see more from her.

Ilya Repin: Painting the soul of Russia (Petit Palais, Paris)

The only big museum show - and the only show from outside London - to make my list was this kitchen-sinking retrospective of the 19th century Russian master.

The show is awesome in scope - Repin was active as a young man, when he painted the study pictured above in Paris, attained fame and patronage as the century wore on, painted Tolstoy (a close friend), several Tsars and Kerensky through revolutions and war, before ending his days in exile in Finland, dying in 1930 embittered and poverty-stricken, unable to afford large canvases and painting on lino instead.

I wasn’t very familiar with Repin’s work before I attended, but I left dreaming of seeing more from him. One day, in the Tretiakov collection in Moscow, whose stacks of Repins were plundered deeply for this Paris retrospective.

Other highlights

Here are five other shows I saw and loved that didn’t quite make the cut:

- Queer as Folklore (Gallery 46)

- Sam McKinniss: Country Western (Almine Rech)

- The Forest (Parafin)

- Prunella Clough and Alan Reynolds (Annely Juda Fine Art - again!)

- Paula Rego (Tate Britain - not featured on Artangled, what was I thinking?)

Disappointment of the year

No knock on the stunning and revolutionary work on show, but I have to say that The Making of Rodin, on at Tate Modern over the summer, was pretty much a curatorial disaster. It was overlong, meandering, and the Tate’s don’t-touch-peasants habit of roping off its works was taken to absurdly hostile new heights. Often, sculptures were not only raised on plinths, but encased in what looked to be perspex boxes, ostensibly to protect these fragile works, but ultimately to distance them from the viewers.

To 2022!

I can only hope in the year to come that the withholding of art from viewer - the live version I mean, not mediated through the COVID-safe layer of a proxy server and a computer screen - will fall away. The Tate rope and perspex box will be cut and removed, galleries will stay open, and I can see more and more in 2022!